The biggest misconception about the words is to presume that they have an inherent and immutable, “objective” meaning. They don’t. The words you and I are using daily have surely changed their meaning over the time. And the way they have changed it reflects how our thinking has evolved. Or degraded, depending on your perspective.

In the modern English, the word “revolution” refers to an abrupt, linear change, more often than not in politics. Things transform to never return to the original status quo: that’s what makes for a revolution. A truly revolutionary event constitutes a radical break with the past. And yet, etymology of this word suggests that its original meaning used to be exactly the opposite.

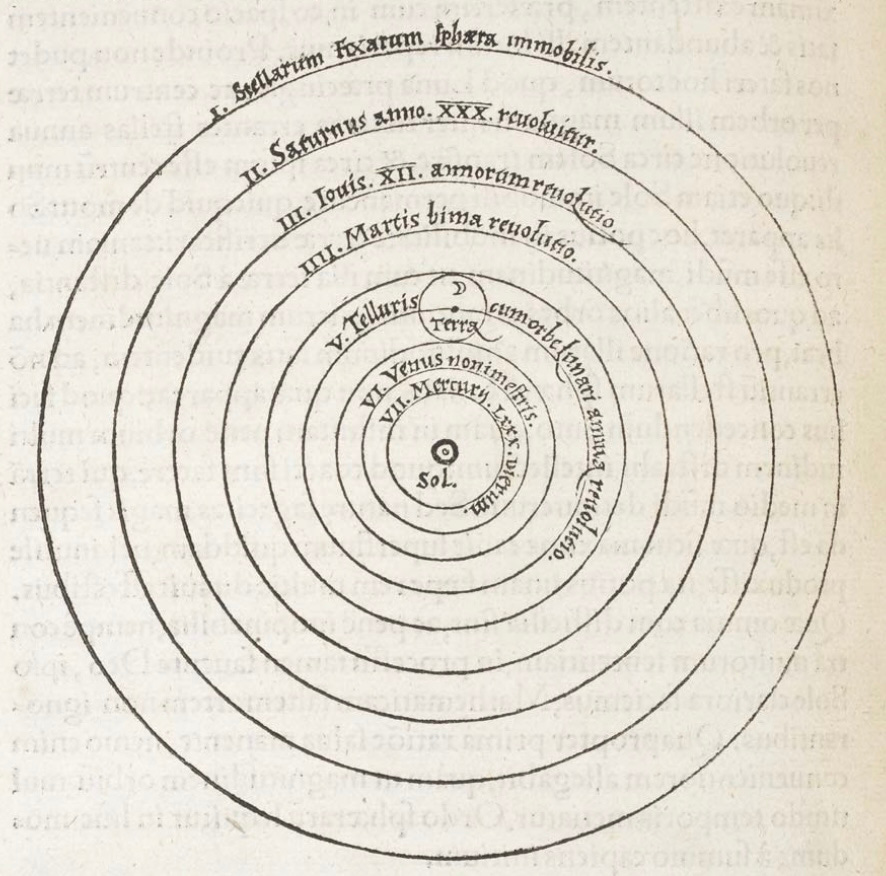

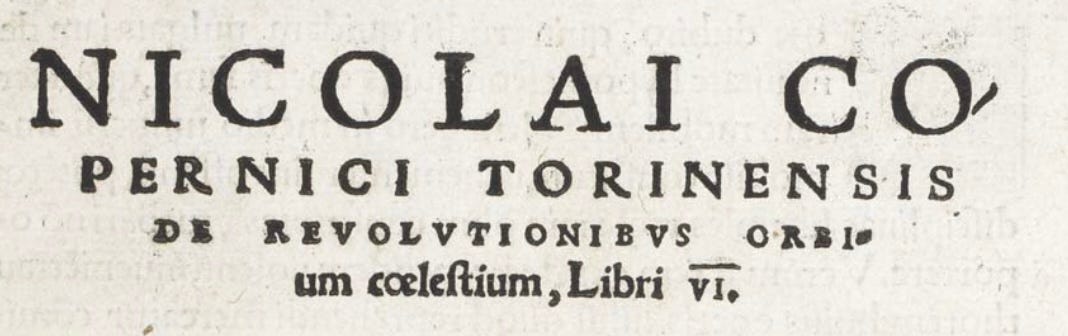

Revolution. Something that revolves. Originally the Latin word revolutio meant “rotation”, referring to the circular motion of celestial bodies. A planet makes a full rotation around the Earth (and later, Sun) only to return to its original position: that’s what constituted a revolution for the medieval to early modern literati.

While the originally astronomical term gradually diffused into politics, it was still associated with circular, rather than with linear movement. The revolution was a political upheaval that culminated in a return to the original state of affairs. The established hierarchy comes into motion, makes a full rotation, and returns to where it used to be, just with different people in charge. Personalities change, the political order doesn’t. That’s what constituted a revolution for the early modern politicians, thinkers, the press.

When the early modern authors said “revolution”, they actually meant a “coup”.

Consider the following example. In 1762 the Russian emperor Peter III was overthrown by his wife who would become Catherine II or Catherine the Great. That was a largely peaceful transfer of power, involving only a very reasonable amount of bloodshed. While Catherine produced the absolutely dehumanising description of her late husband, she confirmed most of his reforms and followed most of his policies. Rhetorics aside, the coup was not about how to run the country. It was about who is the boss.

Ultimately, the coup resulted in Karl Peter Ulrich von Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp (also known as Tsar Peter Fyodorovich) being replaced by Sophie Friederike Auguste von Anhalt-Zerbst-Dornburg (also known Tsaress Yekaterina Alekseevna). One Northern German aristocrat replacing another.

Not much difference, to be honest.

After a full rotation, the system returns to the original position, just with a different person on the throne and the different interest groups around it. That’s what made for a true revolution.

It was only with the French Revolution that the meaning of this term started to change, and to change all across the European languages. The events in France did not only change the world. They also changed the word they are now forever associated with. “Revolution” which once referred to the circular motion of celestial bodies now describes the linear movement of the earthly ones. Things change and never return to how they used to be: that’s what makes for a revolution now. As a result, this word acquired the connotations completely antithetical to its original meaning.

A paradox. Two meanings of the word “revolution” are just so completely opposite to each other that they seem to be barely connected. And yet, there is a connection in between. The revolution which is to lead to the abrupt, linear change had been hardly planned or seen as such on its early phases. Developments we retrospectively frame as revolutionary were rather an unforeseen, unintended consequence of what was initially presumed to be a regular, rotational motion.

A linear revolution is a circular revolution gone wrong.

To be continued

Although the English-speaking press doesn't honor the conventions at all, in the academic world at least there's a line drawn between a true revolution that involves an actual change in the system of government, and ones that simply usher in a new regime under the same political system. Which I'm guessing traces back to de Tocqueville's works on revolutions, which are mostly forgotten after you leave college.

So you're going to have a lot of semantic work to do for most English-speakers, since most folks aren't aware of where the lines are supposed to be drawn between a change in the political system and simply a new ruling elite.

And to shanghai your metaphor a bit, usually in historical terms revolutions simply spin in a circle, but sometimes they rotate enough to cause the extant system to spiral upwards in complexity. So it's still a revolution, just one that spins up into a higher plane.

For instance the Protestant Reformation was another revolution that resulted in the eventual change of an entire socio-political system, but it didn't move past the old ways so much as push for additional complexity and force another layer for personal meaning onto exegesis, instead of simply just trusting the authorities.

Full revolutions create the illusion of moving past the old, but really they just force increasing layers of complexity. Donald Trump's allure would've been the same 100,000ya as it is today, despite the differences in political systems.

cf "Sors immanis et inanis, rota tu volubilis"