Disraeli instructed us to read no history but biography1. I would modestly propose an amendment to this maxim. Read no history but family biography.

Individual life is short. There is not much you can do2. To accomplish something big, you need to accumulate incremental achievements over a few generations. Step by step, fathers build the foundation for their sons to stand upon. It is for the sons to play big. But their chance to play is based on the ancestral sacrifice.

Contrary to the widespread opinion, the meritocratic principle does, indeed, work in practice. It is, however, best visible in the long run, over the lives of several generations. And that is because it is the family rather than an individual that makes for a basic unit of social mobility.

As Joseph Schumpeter pointed out:

‘‘Not only does modern capitalism proffer means to shelter and nurse almost any kind of ability … but by the very law of its structure it tends to send up the able individual and, much more effectively, the able family’’

(Joseph Schumpeter. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy)

Not so much an able individual, as an able family will be sent up.

And, perhaps, no family can illustrate this principle better than the family of Vladimir Lenin. His grandfather was a fugitive serf who made himself a free townsman. His father was a townsman who made himself a nobleman. And he was nobleman who made himself a dictator. From serfs to townsmen, from townsmen to noblemen, from noblemen to dictators, all in three generations.

That was, beyond any doubt, an extraordinary family; a brilliant example of meritocracy, of upward social mobility, and of the socio-political effects they produce.

Grandfather

Nikolay Ulyanov was born in 17683, as a serf.

And when I say “serf”, I mean a “plantation slave”.

In the late 18th c., serfs made for over 90% of the Russian Empire’s population. Most were villagers, living in the countryside and working on the aristocratic estates. Serfs had little legal protection or personal autonomy. They were bought and sold, mortgaged and auctioned. They could be sold by the entire villages, they could be sold individually, they could be sold far away, separated from their family and their kin.

It didn’t become like that overnight. In fact, the state and the status of peasantry worsened progressively, for generations4, until it finally hit the bottom. The reign of Catherine II (1762-1796) was the darkest age of peasantry, the lowest point in the history of the Russian commonfolk. By that time, it was the chattel slavery, in all but name.

And Nikolay Ulyanov had a misfortune to be born in the age of Catherine.

“Bargaining” by Nikolay Nevrev. This painting is supposed to present the 19th c. realities.

There was, however, a nuance. Serfs had no rights, and could be all used as plantation slaves. And yet, the plantation mode of economy could be more profitable or less profitable depending on the soil fertility.

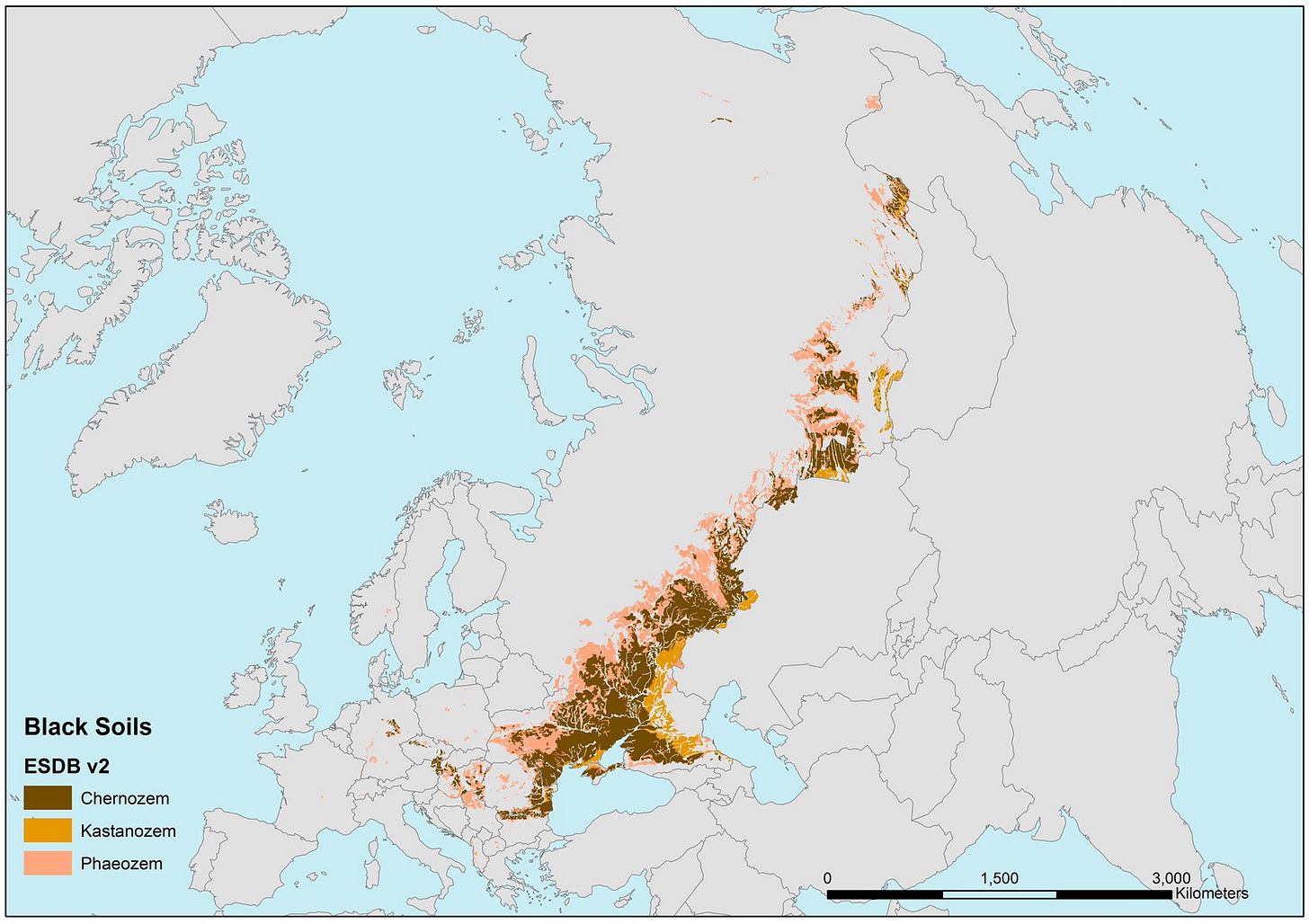

To understand the history, you need to understand geography. And to understand the Russian geography, you need to internalise one crucial dichotomy:

Blacks Soils vs Non Black Soils. Which means the Fertile South vs Infertile North.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to kamilkazani to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.