How I understand the history of China

Your life has a limit but knowledge has none. If you use what is limited to pursue what has no limit, you will be in danger.

(Zhuangzi, Watson’s translation)

Below is the list of ideas I use to structure the logic of Chinese history

Perhaps, you may find them useful as well

North China is the Original China

Chinese civilisation started in the North.

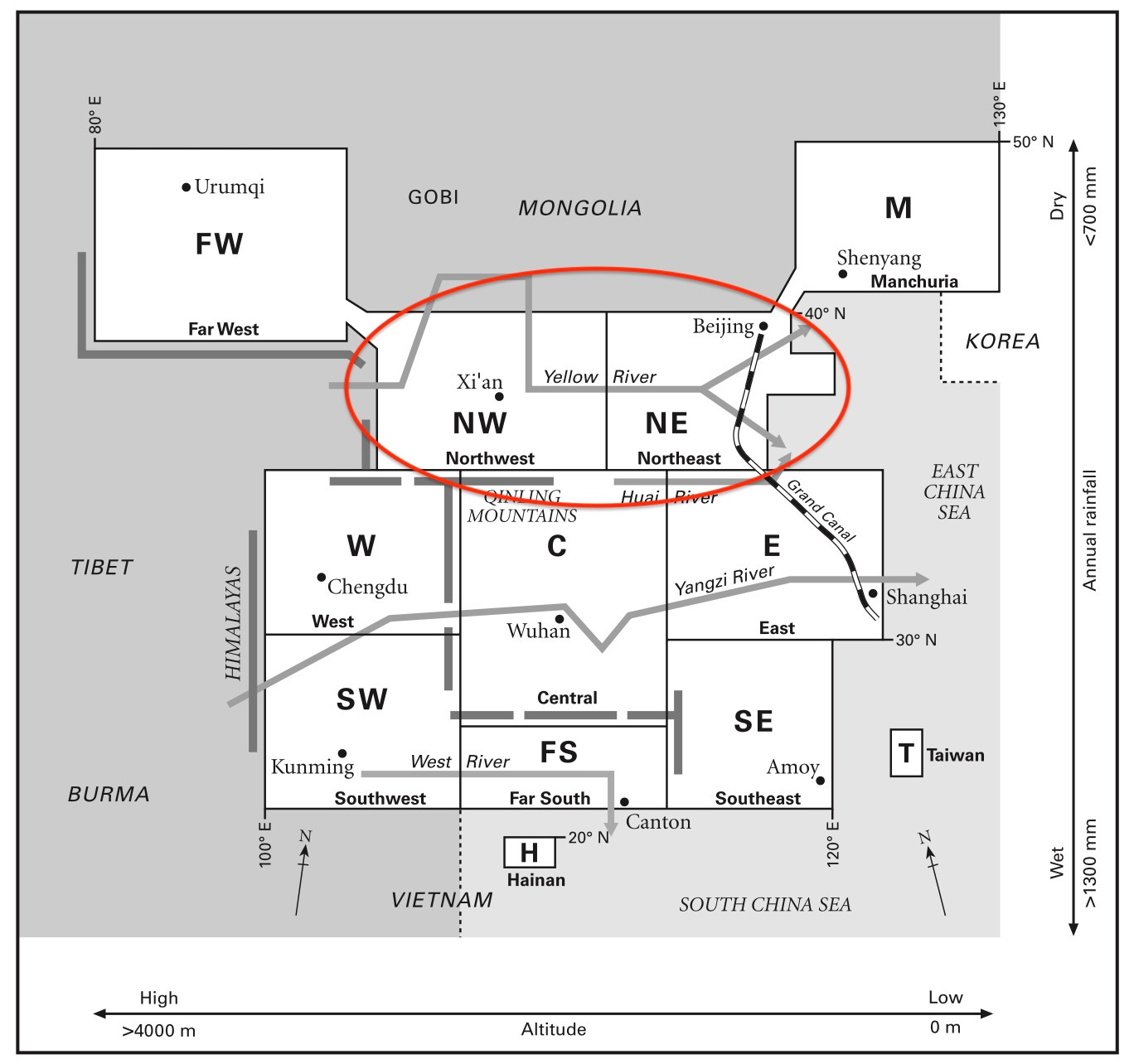

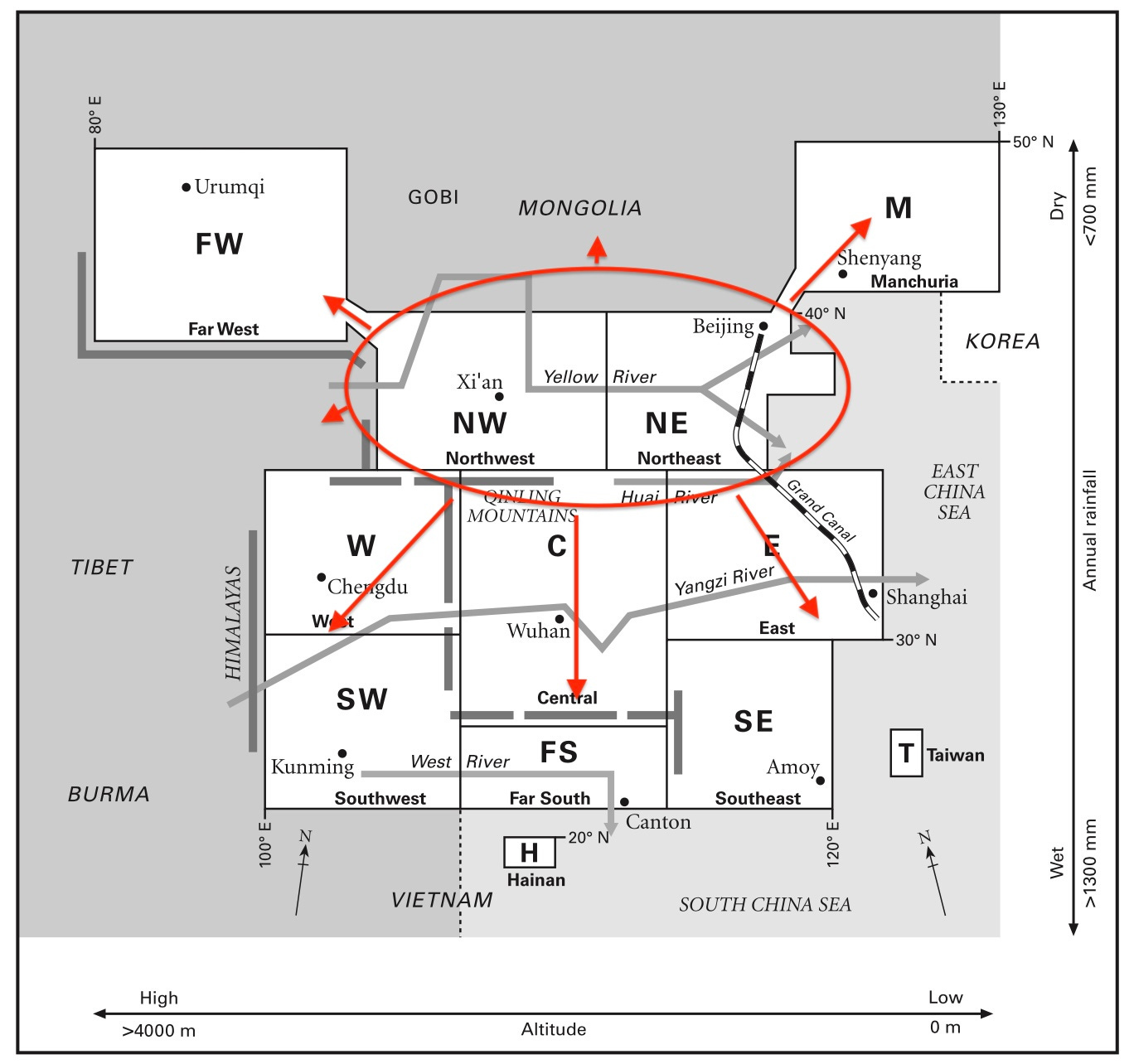

On the map below, the North would correspond with the NW and NE quadrants

The Yellow River basin. That was the original cradle of Chinese civilisation

Everything else, is a later addition

I really like this map from Mark Elvin’s Retreat of the Elephants

From the North it expanded elsewhere

From the original cradle in the North, Chinese demographic expansion went, well, in all directions really.

It is only that some directions proved to be less successful, historically speaking. Most of the regions bordering the original cradle of Hua more or less suck in terms of the climate, water availability or the opportunities for agriculture. That includes the northern, western and even the northeastern direction1.

The best, the most important and the most consequential direction of the Chinese colonisation (from the original cradle on the Yellow River) has been the expansion in southward direction. It was the southward expansion that created the modern China, for the most part.

NB: Still, it is important to remember that the South is a later addition that outgrew the North only recently. At this point in history, combined population of the South exceeds that of the North. This had not always been the case. In fact, for most of Chinese history it had been the other way around. The North is where most of the people lived, historically speaking.

South China is an amalgam of the aboriginal peoples and Chinese colonists

Expanding southward, Chinese colonists encountered the aboriginal peoples, speaking the Thai-related, Viet-related, Austronesian and many other languages including the Sino-Tibetan. The colonists have been partially massacring, partially subjugating, partially mixing with, and partially displacing the natives.

Now the neat part is.

Displacement of the natives did not necessarily proceed only horizontally, from one district to another, from what is Central China to the Southwest and from what is now Southwest - across the mountains to the South East Asia.

But it has also proceeded vertically, from the lowland more suitable for the grain agriculture, further and further up in the mountains. The colonists were driving the locals from the most fertile and easily cultivable land. But they might not really stop them from taking the badland up in the hills.

In the hills of the south, and especially southwest this created some sort of the vertically sliced society. In the lowland, there lives a mix of the colonists with the locals. Further up, in the inaccessible highland, you can find more and more authentic remnants of the past.

Civilisation of North China is discontinuous

We tend to see China as the eternal, implacable, constant monolith where nothing ever happens

Nothing can be further from truth

In fact, civilisation of Northern China, the original cradle, is highly discontinuous. From time to time, it breaks down. It is debatable whether we should attribute these periodic collapses to the Inner Asian invasions, or to the internal crises. Perhaps, there is an element of chicken and egg problem here.

The fact, however stands. Once in a while, civilisation of North China collapses. These collapses tend to include the massive demographic contraction (people die, flee, or flee and die), loss of urban centres, of literate culture, of written documents.

A number of these collapses have been truly apocalyptic both in terms of the human death toll, and of the cultural loss. People lost, literati lost, writings lost. All lost.

The Dark Ages commence

Civilisational collapses trigger the cultural change

After each Dark Ages phase, the civilisation re-emerges again. Population grows back, towns and cities get rebuilt, and a new dynasty consolidates control over the region. To buttress their rule, they create a new bureaucracy, and cultivate the new literary class.

Now the thing is. This new literary class does not have direct continuity with the past. Because the continuity had been interrupted by the Dark Ages. By the end of the Dark Ages, everything had changed. Much of the old population had died, most of the old elites.

Whatever people live on the plains of the North, they now hold a different culture, speak on the different tongues (= spoken vernaculars), unintelligible for the people of the past. Whatever identity, and literary tradition, they will build, they will build it on the ruins, of the old one, long gone by that point.

To build their legitimacy, the new dynasty, and the new elites will always present themselves as the direct successors of the old ones. This, however, should be understood figuratively, more as an affirmation than as a representation of the objective reality.

Thing about the Roman Empire. It was gone in the apocalyptic chaos of the Migration Period. Then, there came the Dark Ages. Much of the population, and disproportionately urban population died, or was dispersed. The old civilisational centers were abandoned. The old culture was gone. The old language was gone.

Centuries later, the new elites, of the new, different polities that re-emerged on the ruins of the Rome, claimed back the Roman legacy, and the Roman identity. They called themselves Rome. They claimed the direct continuity with Rome. They re-appropriated the Roman language (= Latin), and used it to write their own laws, and narratives.

But they were not Roman, or at least, not quite the Romans, not in the old sense. Even their language was different. When the medieval monks and clerics re-appropriated Latin, they did not appropriate in the old form. They changed it. Hence, the relative incomprehensibility of the Medieval Latin. Medieval Latin is when the monks who do not actually speak the Latin (remember, the old language is dead, by that point), and speak on the different vernaculars, try to write and express themselves in Latin.

Yes, they make an honest effort. But what you have as a result will be very, very different from the language of the yore. So, in terms of the literary language you will have something like this:

Classic Latin → Dark Ages → Medieval Latin

With a loss, and a subsequent re-approriation, by the new people, afterwards.

Now it looks, like the Chinese literary language had a least a few of the equally significant transformations in the course of its history.

One would be the Han-Sui interregnum. The Han Empire collapses, the population collapses, the urban centres collapse, the literary classes collapse. By the time Sui dynasty consolidates control, more than 350 years later, everything had changed, included the spoken tongues. So, when the scholars and the bureaucrats of the new dynasty dig into the old texts, they treat them not unlike the medieval monks treat the texts of antiquity2.

The Sui literaty re-appropriating, re-interpreting and re-inventing the old literary language for the intellectual and administrative purposes, brings to life the new one, the Middle Chinese. So, in terms of the high culture and literary language, you will have something like that:

Old Chinese → Dark Ages (Han-Sui interregnum) → Middle Chinese

With the cultural loss, re-discovery, and re-invention in between.

Then you have another apocalyptic event. The Mongol storm. Again, the old civilisation gets burned to the ground, with its cities, and its literati.

Then, again, civilisation re-emerges. By the time, the new dynasty (Ming) consolidates control, everything has changed again, including the spoken tongues. To run their state, write their laws and their narratives, the new dynasty re-appropriates the literary language of the past. Which, again, will be only half comprehensible to the new guys. So, in the process of re-appropriation, they effectively re-invent it. Much like the medieval monks

Middle Chinese → Dark Ages (Mongol Storm) → Literary Chinese

Please keep in mind that I am discussing the change in the literary language, and not in the vernaculars, the tongues spoken on the ground. They, meanwhile, have their own evolution, and their own mutations.

Now the thing with the written language, the characters, is that most of them tend to have both semantic and phonetic component in them. Basically, most of the characters give the clue about how they are supposed to sound. If we could use it, Chinese language would be much, much easier to learn.

Unfortunately, we can’t. And that is because the clues refers to the old sounding in the old, long forgotten vernaculars of the past. They refer to how it was supposed to sound hundreds, or thousands years ago. By this point in history, the spoken vernacular has changed completely. The old sounding, we don’t use.

All of this must have been adding to the incomprehensibility of the old culture for the each post-Dark Ages generation, and added greatly.

Conclusion

So what you have after each civilisational collapse, is that the old culture, and the old society, is gone. When the civilisation re-emerges, after the Dark Ages, it speaks the new spoken languages, it re-appropriates (= re-invents) a new literary, written language. It works out a new tradition, claiming to be the successor of the old one, but having no direct continuity with it. It is in fact a different, very different organism, both politically and culturally.

Every collapse, every Dark Ages, bring to life a new culture:

Han 1.0 → Dark Ages → Han 2.0 → Dark Ages → Han 3.0

Something like that.

Every new culture is built on the ruins of the old one, from the scattered shards of the old one, and may, perhaps, be only distantly similar to its predecessor.

And then, this new culture, starts the new wave of the territorial expansion and consolidation. The colonists expand in all directions, but most importantly, southward.

In the south, they face locals. The natives, the tribesmen. They conquer them, they massacre them, they subjugate them, they displace them from the fertile lowlands, far away or further up, into the inhospitable and infertile highlands. The lowland is taken by the new wave of the colonists, and only up in the hills there remain scattered remnants of the past.

So now the paradox is

Many of these natives are not natives, actually. To a very significant degree, they represent the earlier waves of the Han colonisation.

When the Han comes to the south (again), it is not the old Han. It is the new one. Let’s say Han 2.0. So when they come south, and face some mix of Han 1.0 and the natives, they can’t tell between them. They can’t really distinguish one from another. What they see is just natives, perhaps, only superficially sinified.

Their sinicisation may not be superficial, actually. It is very possible that the locals actually preserve the old culture of the North in a truer, more authentic form. Far more authentic, compared with the new, evolved memes of the North.

But the newcomers don’t know, and don’t realise it. They see the locals as natives

And treat them accordingly

There have been many waves of the colonists going northward (northeastward/northwestward). For the most part, they died and that’s it.

Because the cultural change had been just as great, and the distance with the past, at least as vast.

Ive never heard before the idea that Southern Chinese were displaced by reunification dynasties. The South took over as population center during the Song, 1000-1100. Indeed it became the southern song because they lost the less populous north. The south grew 3 rice harvests a year from a champa rice hybrid from Vietnam or Cambodia which tripled Song population. The idea the south were so foreign that northern Chinese came down to massacre and displace is ... well any evidence? Because ive never heard this before.

Your central idea, stated a few times is that Chinese civilization died every dynastic fall and that Current china's ideas of their own continuity over millenua are just nationalist lies.

But there's other example. Greece's culture has Byzantine religion and language and Greeks feel descended from it. Demotic Greek is certainly different, the written language has shifted a bit, but its still there. It wasn't abolished by 400 year ottoman period. Southern China having so many millions more probably kept it's culture together through the darker times. After all, Han Chinese culture itself was formed during spring and autumn and warring states, even "darker" for chinas actual people then interdynastic periods. Those periods China was just divided the way it was for centuries before Shi Huangdi 's Qin Unification. "5 dynasties" and "12 kingdoms" disunity.

And in any case by Mongol era, south is much more populated. The colonization would be going south to north.

Thanks for this. I finally sat down and went through the whole history of China so I could get a good geographical outliner (similar to that provided by the McEvedy atlases for most of the world -- but he died before doing China). My conclusion: yeah, this is about right from an aerial-overhead satellite-image-height abstraction point of view.

The semi-exceptions to the pattern of waves of conquest coming out of Northern China are the dynasties of the Song (coming from the Yangtse, so not really from the north, but not from the south either), a couple of others out of Nanjing (or other Yangtse areas, who again mostly lost), Yuan (Mongols), Qing (Manchu/Jurchen), and arguably the KMT (from Guangdong, but they lost). But they're mostly not exceptions to the pattern of outward colonization where "China" is Beijing-Xian and the rest of it is colonies of various eras.

The southern coast really has been repeatedly conquered by Northern China, and treated during the conquest as an area filled with foreigners. The "first emperor" of the Qin dynasty was the first to do so, of course, violently conquering the entirely non-Chinese Baiyue, so this has been happening for some centuries.

During the Northern and Southern Dynasties period, government was split between Yellow-River-based countries and Yangtse-River-based countries, with the southern coast still being an area still largely of non-Han background, being colonized and subjugated by Chinese colonists. Eventually a Yellow-River-based group (Sui) defeated the Yangtse-River-based overlords of the south.

"It was during the Northern and Southern dynasties period that the earliest recorded mass migration of ethnic Han to southern China (south of the Yangtze River) took place. This sinicisation helped to develop the region from its previous state of being inhabited by isolated communities separated by vast uncolonized wilderness and other non-Han ethnic groups."

"During the Northern and Southern dynasties, the Yangtze valley transformed from a backwater frontier region with less than 25% of China's population to a major cultural center of China with 40% of China's population, and after China was subsequently unified under the Tang dynasty, they became the core area of Chinese culture."

-- Wikipedia on Northern and Southern Dynasties.

So, Chinese colonial expansion. Anyway, the southern coast (Pearl River Delta, Fujian, what's now northern Vietnam, etc.) was still ethnically non-Han at this time, and appears to have been colonized primarily during the Tang imperial period. When the Tang empire collapses, the south breaks up along natural lines during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (the Ten Kingdoms being logical polities), before being reconquered by the Song. The Song imperium lasts until Kublai conquers everything north of Vietnam.

Guangdong was colonized early enough that the descendants of the colonists are "native" now. But there's still a colonization-displacement history there.

There is still conflict between the descendants of aboriginal inhabitants of India (now "scheduled tribes") and the descendants of the Indo-European invaders of *1400 BC*. Guangdong was primarily colonized 1000 years ago, which is much much later than that, though the cultural merger and "sinicization" has been more thorough.

BTW, the whole history fits the pattern of agriculturally productive areas with no birth control creating excess population which spills out in waves of colonization. (Also notable in Europe, as you've noted.) This means it's going to END now that they have birth control.

China (Beijing/Xian) is a colonial-settler empire just like Russia (Moscow) or France (Paris) or England (London) or Spain (Madrid) or Portugal (Lisbon) or Rome (uh, Rome) was. Not an uncommon thing. (Tibet and Xinkiang, late conquests, were conquered by the Qing empire during the European colonial giant-empire-building period, just like Vladivostok or Mexico or India; the Chinese imperial control was reasserted in the 1950s around the time Stalin was reasserting control over the rest of Central Asia; it's all the same.)

But most of the colonial-settler empires have decolonized, decentralized, and broken up in the modern era. Even the areas dominated by the descendants of colonists (South America, North America) or who speak the language of the colonizer (Ireland) tend to leave the empire, because this is not an era in which empires are practical.

This is, put bluntly, an era of small countries and breakups of empires. This was evaded in the Chinese Empire by extremely competent technocratic management by Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao -- nobody wants to leave when you have a *competent* government -- they're rare enough! I don't think it'll survive Xi Jinping, who isn't competent, and who is actively alienating practically everyone in numerous ways while making himself dictator. The post-Xi government, if it was particuarly competent and friendly, *might* manage to reconquer all the territories currently controlled by Beijing -- but that really isn't the military-geopolitical trend for the last 75 years. The current state of tech appears to mean more countries, not fewer. It's not a trend which a sensible leader would oppose. Loose federations like the EU seem far more viable than large countries.

There are four oversized empires which have yet to break up: Russia, the US, China, and India. The odds that any of them survive much longer is low. Some may break up *de facto* rather than *de jure*, just like the Holy Roman Empire existed for centuries after it stopped really being a country. (India's many repeated rounds of decentralization and transfer of power to provinces, which have also been repeatedly reorganized around linguistic and cultural communities of interest, is a sort of highly effective preemptive strike against national breakup -- if you already have autonomy, who needs independence -- although Modi's attempts at centralization make national breakup more likely.)